The Journey and Cost of Success

Episode 26 - How Bakuman changed my perception of success. Discussing the Japanese idea of pursuing your dreams, sacrifice and the tragedy of Karoshi

Greetings,

Hope you’re doing well. Welcome back to the campfire. If you listen closely, there are faint, intimate and sweet whispers in the distance. There, just beyond the treeline. I know it’s dark and difficult to see.

To see ahead, eyes are not enough.

Think deeply on this.

I wanted to be a Mangaka

You wanted to be a what?

A ‘Mangaka’ is a Japanese term that indicates an author/artist and creator of Manga, a traditional Japanese type of comic book, quite well known all over the world at this time.

My teenage years marked the transition between one level of consciousness to another. Because that’s what happens. Among the many things that symbolised this event were my encounter with manga and anime, and Japanese media and stories. They have thoroughly shaped me. In very beautiful ways, I might add.

Many of my current stories draw a lot of inspiration from this time and from the incredible stories that I had the honour of encountering: stuff like Naruto, for example, was profoundly impactful and inspiring. I don’t think I would’ve attempted my journey across Europe and into the UK on a one-way ticket if it hadn’t been for the philosophy of Naruto: follow your dreams at any cost. ANY cost.

And so I think what inspired me to create my own stories and art was precisely this power that the Naruto story had on me. I think I wanted to inspire others in the same way I was inspired.

It was also the fact that manga/anime usually have more mature storylines compared to my previous experiences watching cartoons on TV as a child. Instead of superheroes saving the world all the time, manga dealt with complex characters struggling with issues of life, death, depression, growth, sacrifice and fairly engaging philosophy. Even when they fought each other with huge swords it (usually) had a deeper meaning behind it.

But why a Mangaka?

Japanese Manga, unlike Western comic books, are usually (though not always) authored by only one person. This makes it an extremely personal work that combines illustration and storytelling. This level of control over a work of art has always been a cardinal element of my life as an artist. Even to this very day, I have always refused to compromise on Anything when it comes to the creative process.

And so as a teenager I imagined myself travelling to Japan and working as a mangaka. Of course, that never ended up happening and for very good reasons. I’m actually grateful that dream changed and evolved without sacrificing its core elements.

The life of a mangaka is no joke, and it’s also inherent to the Japanese culture and way of life. To make money out of it one has to be ‘serialized’ in a magazine that sells manga, and aside from the difficult road of reaching that point, one then has to produce one chapter every week or so. But inspiration (or the Muses) don’t work that way. Works such as Naruto or One Piece (still ongoing since 1999), now world-famous brands, are the result of a willpower and work ethic that is hard to comprehend, especially for a westerner.

Bakuman, Art and Manga

Bakuman aims to show this journey of a mangaka.

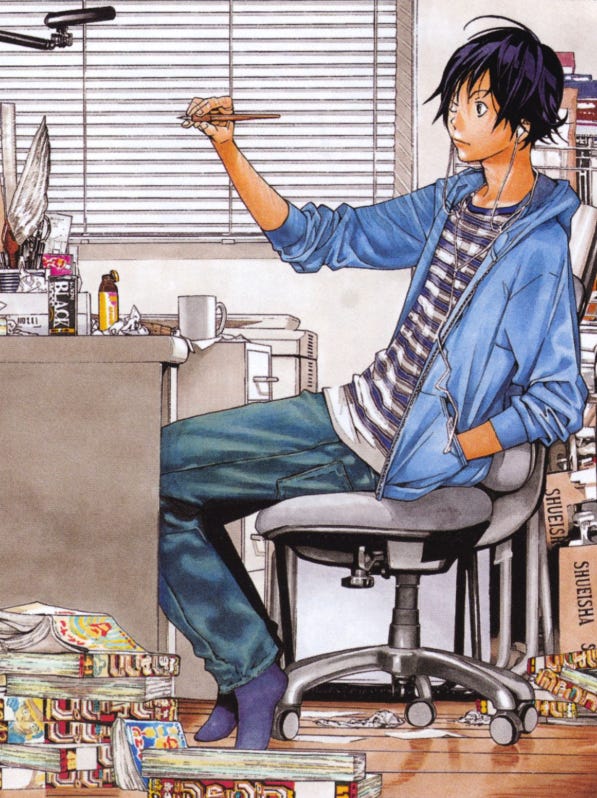

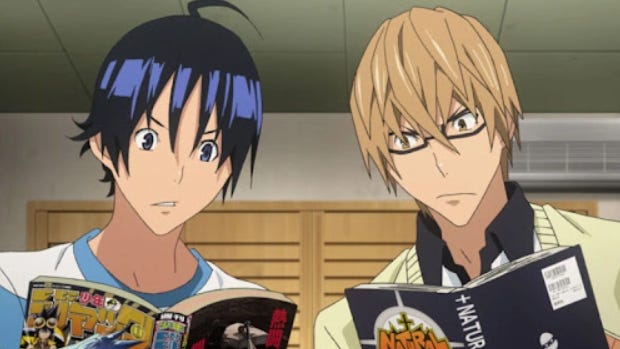

Bakuman is a manga created by Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata, a team also responsible for the masterpiece that is Death Note. First published in 2008, Bakuman is a manga that tells the story of manga. It’s a manga about manga, or about the struggles of what it means to be a mangaka.

It follows the story of two close friends who form a team in an effort to become successful mangakas and it shows the struggles, challenges and sacrifices required to achieve this ambitious goal. It’s also got some questionable teenage romance peppered throughout, but mainly takes topics that all artists have to deal with, such as appeal, marketing, fame/success, visibility, etc. and uses them as structural components in its main premise.

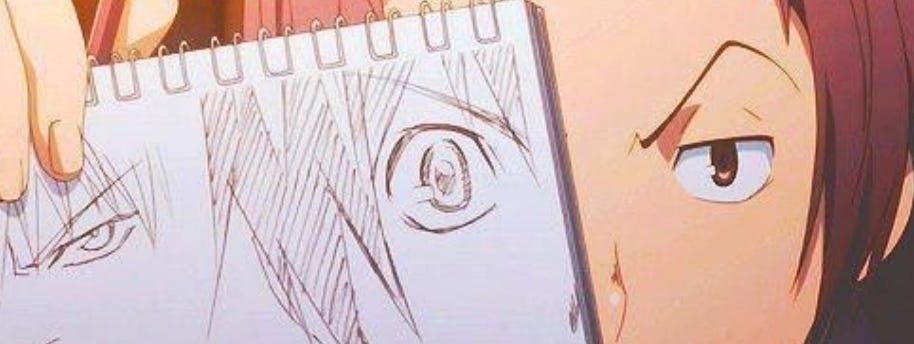

Obata-san, the artist behind this work, has had to draw this manga and also draw the various characters’ own mangas within this manga. This is pretty crazy and extremely challenging, because there are various characters in this story, each struggling with authoring their own mangas and getting them out there. This means that every character has their own unique drawing style (as people do), and that needs to translate within this work alongside the actual author’s style.

I’d started reading this and watching the anime when I was a teenager, but I never got to finish it, and so these weeks I’m currently attempting to fix that. I am not done just yet, but it inspired these words because it has a lot to do with my development as a person and artist.

The journey of these two young men is very difficult and they constantly deal with rejection and the main idea that talent (which they have) is simply not enough. Elements such as mass appeal, style and consistency are often shown to be more important than artistic merit. At one point in the story they face off against a musician who had started drawing a particular type of extremely niche and creative manga, which all characters criticize because ‘it doesn’t fit manga’.

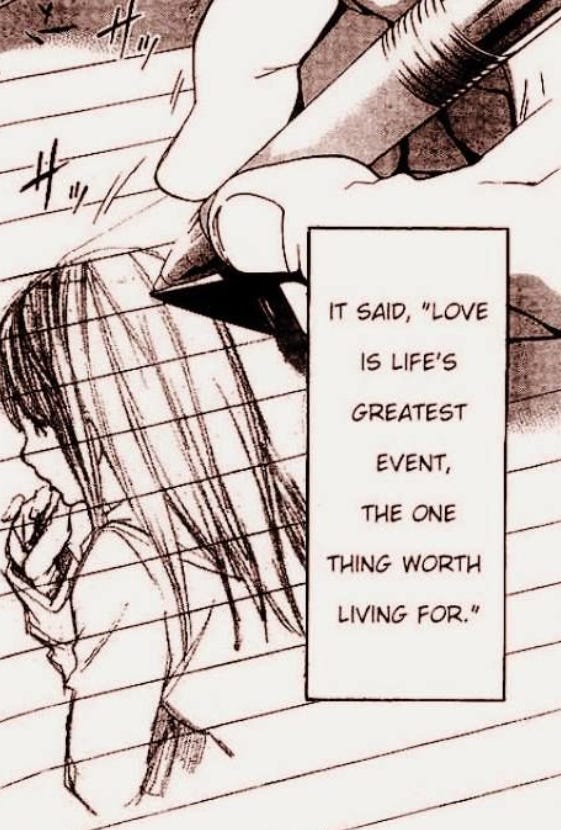

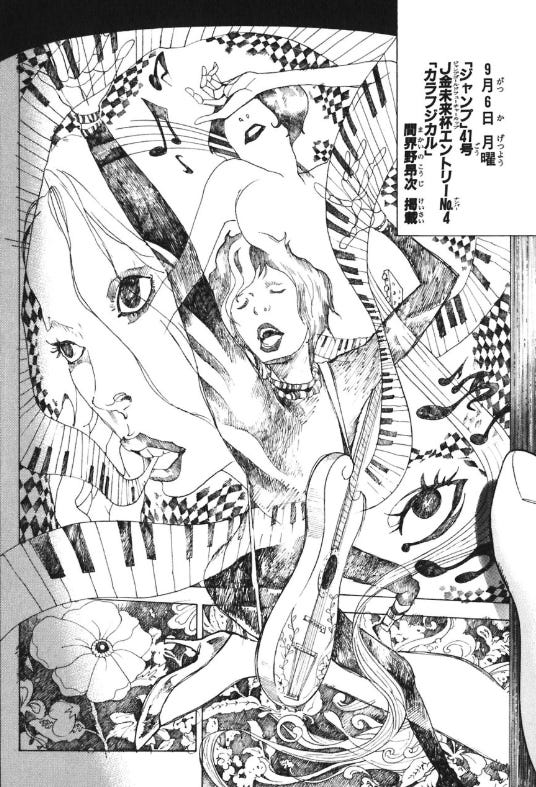

Below is an example of his style:

I reproduce it here because I find it super-fascinating to see what the author of the manga imagined as what another manga author would imagine and draw. Trippy.

To Live and Die for the Dream

One of the main themes of Bakuman is the idea of self-sacrifice. This is a huge part of the Japanese mindset and culture. To achieve your dreams you must sacrifice all your waking hours to the pursuit of only one goal. This is a core idea of Naruto too: that a dream/goal/vision is essentially more important than any other part of life, and one should sacrifice everything in its pursuit.

In Bakuman, the entire story opens up following the death of a character: the uncle of the main protagonist, who was a mangaka but never achieved success, his work was cancelled and, in his efforts to continue living as a mangaka, died from overwork. Essentially, it was a kind of suicide - though this idea is addressed in the story and dismissed by other characters who refuse to call by that name.

This plot point is, unfortunately, very realistic. They call this karōshi (dying from overwork), a very real social issue that came to light in the 1980 but, obviously, has been going on probably for centuries. This is death caused by heart failure, strokes or suicide due to work stress.

In 2015 a 24-year old employee working at the ad agency Dentsu killed herself, likely due to stress related to her employment. She wrote a note to her mom saying: “Why do things have to be so hard?” A BBC article covers this tragic story Here. It claims there are official reports of hundreds of cases of karoshi each year. Not counting, of course, the unreported cases.

This all may sound quite alien to us in the West, but we should also keep in mind the origins of this. I think it echoes the ancient Samurai (the warrior archetype) in Japanese society. The Samurai lived for the sword and the greatest warriors were those who mastered it fully. This meant complete, unwavering dedication. Nothing else mattered but the sword and the path. This path, more often than not, ended in death on the battlefield.

I wrote more about Bushido, the Samurai as well as death, HERE.

This doesn’t make it right. But we should always keep in mind that the modern world is built over dark foundations laid by ancestors who lived and died in ways we’re struggling to understand. Likewise we live in ways they wouldn’t understand either.

For example the Japanese concept of ‘gaman’ translates as ‘enduring hardship with dignity’. It implies complete devotion and self-discipline. To what? Well, to the future I suppose, the only place where the realised goal/dream lives.

Perhaps here in the West we tend to be a little more lenient on this (and we also tend to die from other causes). We prefer a more balanced approach and I agree with this. There’s no point in reaching a dream if there’s nothing left of the dreamer to enjoy this realised dream.

But there’s also much we can learn in terms of introducing measured parts of the Samurai attitude into our daily lives, without compromising our mental and physical health. I found this very practical for me to learn, especially in recent years.

More to come. And let me know in the comments if there’s any particular parts of this that you’d like me to speak more on.

Blessings,